Peter Feuchtwanger

Society e.V.

"Blog"

Essays & Articles

Welcome to the “blog” of the Peter Feuchtwanger Society. Read through various articles and essays written by our members which are all related to the content of the archive, or simply personal memories of the work and life of Peter Feuchtwanger.All these texts are published with the permission of the authors. All copyrights of the articles and essays stay with the authors.

Deutsch

Susanne von Laun

English

Haydn Dickenson

For more extended information on Peter Feuchtwanger - including photos, and several of his texts and essays - please refer to the multi-language website: peter-feuchtwanger.de

Mozart Fantasie d-moll

Mit Anmerkungen und Fingersätzen von Peter Feuchtwanger

© 2023 by Susanne von Laun

Alle Bilder entstammen der von Peter Feuchtwanger genutzten Mozart Ausgabe:

W.A. Mozart Klavierstücke (G. Henle Verlag, 1967)

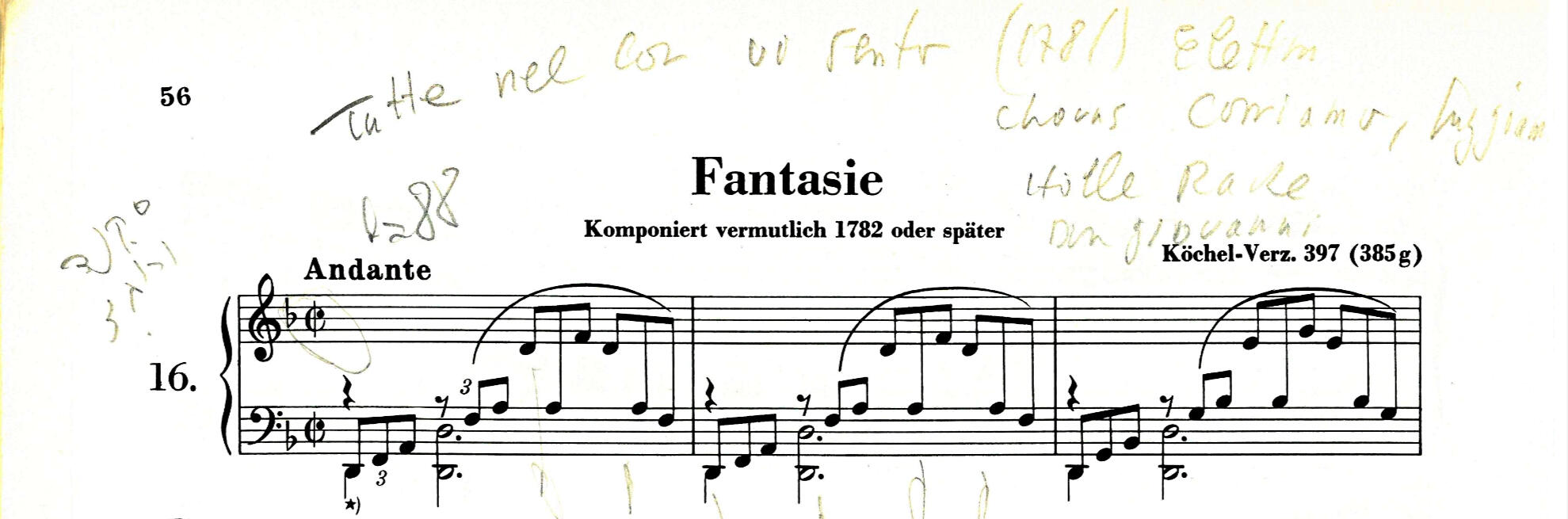

Mozart komponierte die Fantasie d-Moll KV 397 vermutlich 1782, vielleicht auch später, und ließ sie unvollendet. Die letzten zehn Takte fügte Maximilian Stadler hinzu.Vor mir liegt die Partitur der Mozart Fantasie mit Peter Feuchtwangers persönlichen Fingersätzen und Anmerkungen (siehe Bild 1): „Tutte nel cor vi sento" [Elettra] 1781 aus der Oper Idomeneo hat er über den Beginn der Fantasie geschrieben, darunter „Der Hölle Rache kocht in meinem Herzen“, die Arie der Königin der Nacht aus der Zauberflöte, und „Don Giovanni“.

Bild 1

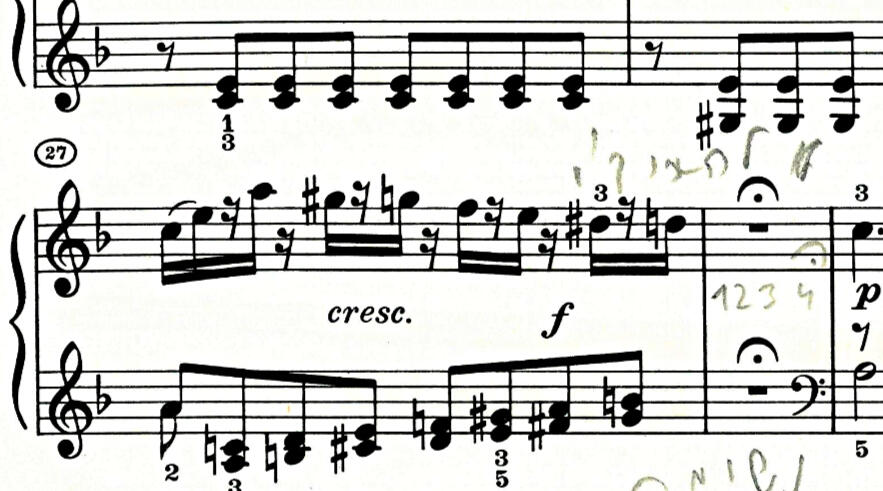

Alle genannten Werke bzw. Teile stehen in d-Moll und haben einen ausgeprägten dramatischen Charakter. Es ist interessant, dass Peter Feuchtwanger die Opern anführt und nicht das d-Moll Klavierkonzert oder das Requiem. Wir könnten ein Gedankenexperiment durchführen und uns die Fantasie als eine Opernszene vorstellen: Orchestrale Einleitung, zweiteilige Arie mit Zwischenspielen und Kadenzen. Es wäre interessant zu hören, wie eine gute Sängerin die Melodie des Adagio singt und wie sie nach dem dreitaktigen Orchesterzwischenspiel fortfährt. Doch ist die Komposition der Form nach eine Fantasie im Sinne von Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach mit improvisierendem Charakter und wechselnden Affekten.Über den drei Formteilen stehen Peter Feuchtwangers Metronomangaben. Er hat alle Pausen und Fermaten sorgfältig markiert. In Takt 28 schreibt er sogar unter die Fermate die Zählzeiten 1-2-3-4 und über die Zählzeit vier eine Fermate (siehe Bild 2).

Bild 2

Peter Feuchtwanger denkt als Komponist und betrachtet jedes Werk aus dem Blickwinkel des Komponisten. Dieses verdeutlichen Pfeile und Verbindungsbögen, die musikalische Zusammenhänge, Hintergrundlinien und Schichten aufdecken.Beispiel (siehe Bild 3): Von Takt sieben an umkreist Peter Feuchtwanger die linienbildenden Noten in der rechten Hand a1 - g1 - f1- es1 - e1 - d1 - cis1. Das cis1, fünfte Note in Takt 9 hat er zusätzlich mit einem Pfeil versehen, der zum Basston d1 des neuen Formteils zeigt. Die Linie wird unterbrochen, das cis1 wird quasi alleine gelassen und dann mit der ersten Note des neuen Formteil dem d1 in der linken Hand, wieder aufgegriffen.

Bild 3

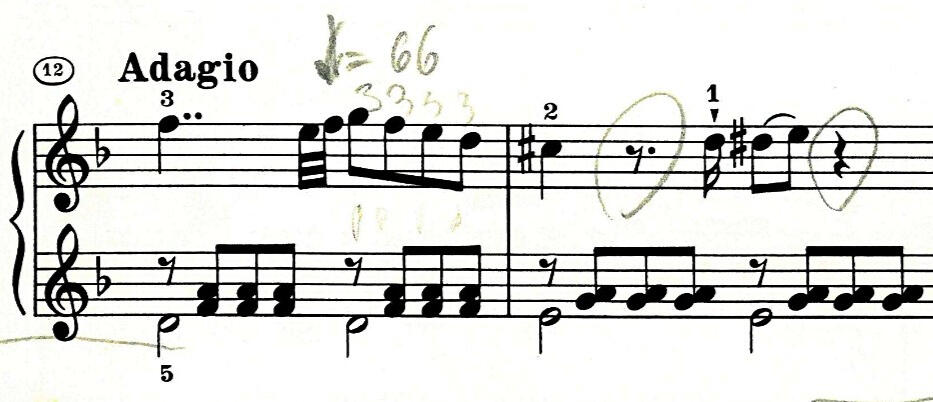

Im Adagio über Takt 23 schreibt Peter Feuchtwanger ausdrücklich und mit einem Ausrufezeichen versehen „non accelerando“ (siehe Bild 4).

Bild 4

Im Allegretto finden wir in den Takten 55, 57 und 58 (siehe Bild 5) jeweils einen kleinen Kreis, bzw. die Zahl Null (“0”) über den Noten, dies war Feuchtwangers Art, „no accent“ zu notieren.

Bild 5

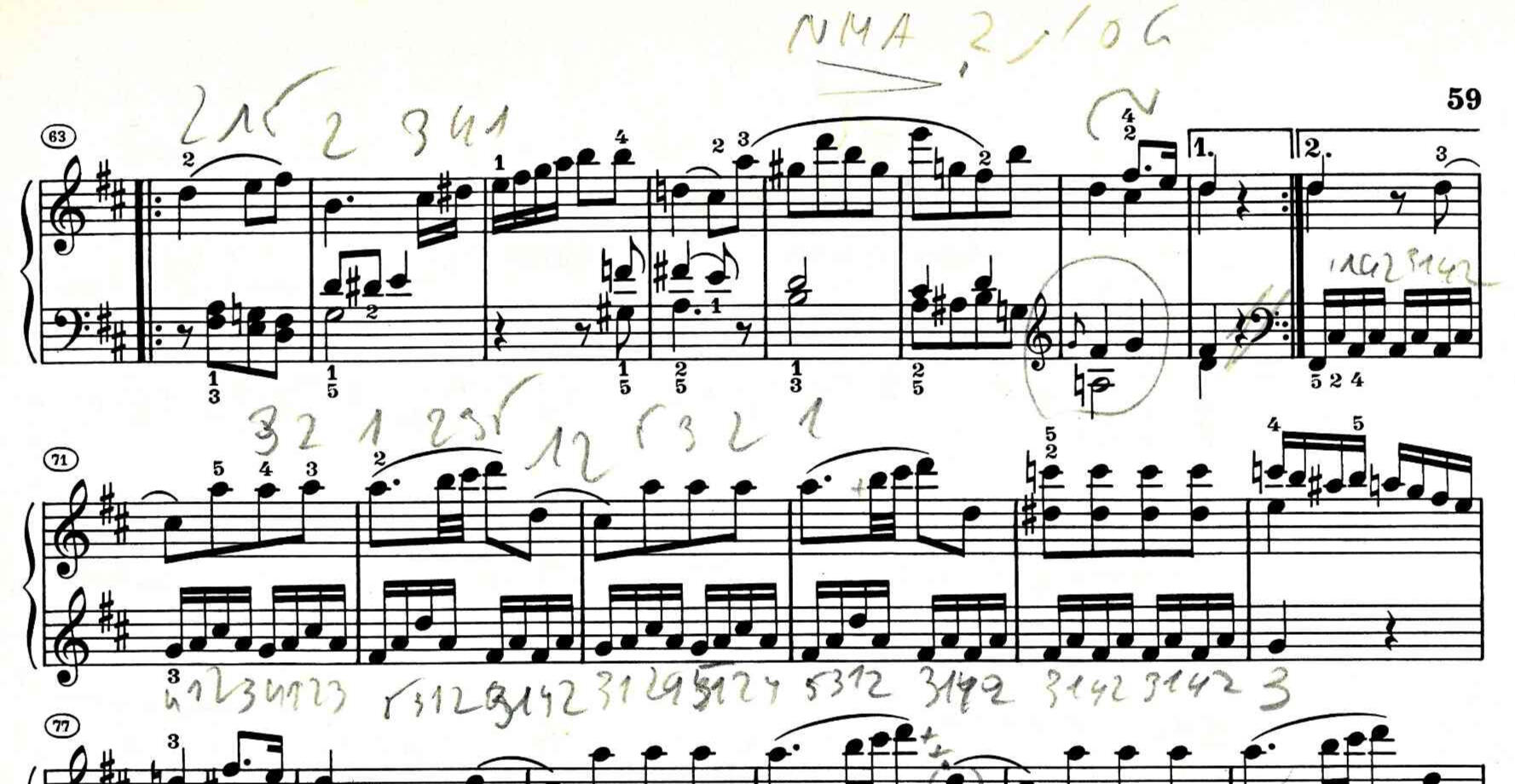

Durch einen Akzent auf der höchsten Note der Phrase, dem h2, und einen auf der zweiten Zählzeit von Takt 58 würde die Linie gestört werden. Es empfiehlt sich, beide Varianten auszuprobieren und herauszufinden, wie sich die Akzente oder Nichtakzente auf die musikalische Linie auswirken.Das Diminuendo-Zeichen - von Feuchtwanger in Takt 67 präzise vom 2. Achtel bis zum 2. Achtel des Folgetaktes gesetzt - unterstützt die Hintergrundlinie a2 - gis2 - g2 und fis2. Das fis2 wird alleine gelassen und in Takt 69 auf der zweiten Takthälfte wieder aufgegriffen (siehe Bid 6).

Bild 6

Es drängt sich der Gedanke auf, die Ausführung sei bis ins letzte Detail geplant, doch ist es das Ziel, die Komposition auf diese Art und Weise zu verinnerlichen. Durch das sorgsame Studium der Partitur spüren wir den Intention des Komponisten nach, um die Fantasie dann so zu wiederzugeben, als ob wir sie gerade erfunden hätten.Einen Fingersatz, der von der Norm abweicht, finden wir in Takt 12 (siehe Bild 7). Die Melodietöne in der zweiten Hälfte des Taktes 12 g2 - f2 - e2 - d2 spielt Peter Feuchtwanger mit dem dritten Finger, um der Melodie einen Portamento-Charakter zu geben, eine Anlehnung an den Gesang.

Bild 7

Chopin hat ähnliche Fingersätze gelegentlich in seinen Stücken notiert. Von Mozart ist mir kein einziger persönlicher Fingersatz bekannt.Gewöhnungsbedürftig scheinen Peter Feuchtwangers Fingersätze der Sechzehntel-Begleitfiguren in der linken Hand Takt 70 und folgende (siehe Bild 6). Kennen wir seine Technik und hinterfragen die Fingersätze, dann finden wir heraus, dass die innovativen Fingersätze sorgfältig durchdacht sind. Sie helfen, entweder musikalische Ideen zu realisieren, wie in Takt 12, oder fördern, wie in Takt 70 und folgenden, eine natürliche Spielweise. Peter Feuchtwanger hat ausdrücklich darauf hingewiesen, dass die Fingersätze geübt werden sollen, beim Spielen aber genommen wird, was kommt, ganz spontan. Mit den Fingersätzen üben wir Bewegungsmuster, haben wir diese erworben, ergibt sich der Fingersatz aus der Bewegung.Fazit: Peter Feuchtwanger hat eine klare, schlüssige Auffassung des Werkes und seiner Ausführung und weiß, diese mit wenigen Anmerkungen dem Leser nahezubringen. Das Studium dieser Aufzeichnungen gibt einen Einblick in seine Gedankenwelt und Arbeitsweise. Sehr lohnenswert für jeden Klavierspieler jeden Niveaus.

Susanne von Laun

Die Peter Feuchtwanger Society e.V. verfügt über ein Archiv mit Aufzeichnungen, Noten, Literatur, Fotos aus dem Nachlass von Peter Feuchtwanger, die nach und nach einer breiteren Öffentlichkeit zugänglich gemacht werden sollen. Weitere Informationen finden sie hier.Ebenso veranstaltet veranstaltet die Peter Feuchtwanger Society e.V. jährlich ein Klaviersymposion in Feuchtwangen. Das nächste Symposium findet vom 02. bis 04. April 2024 statt.Ein Buch & DVD mit Peter Feuchtwangers Klavierübungen im Handel erhältlich.Eine Liste mit Pianisten und Pädagogen, die seine Technik weitergeben, ist hier zu finden.

On Peter Feuchtwanger - Part 1

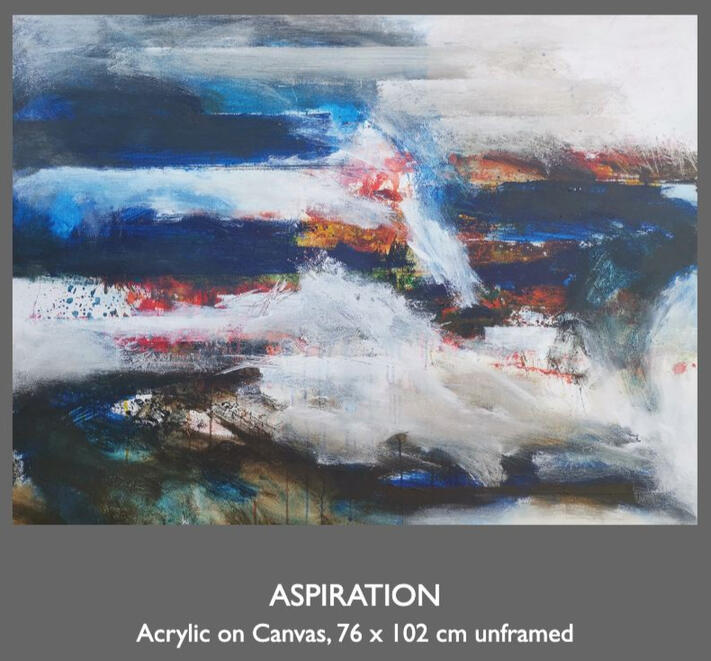

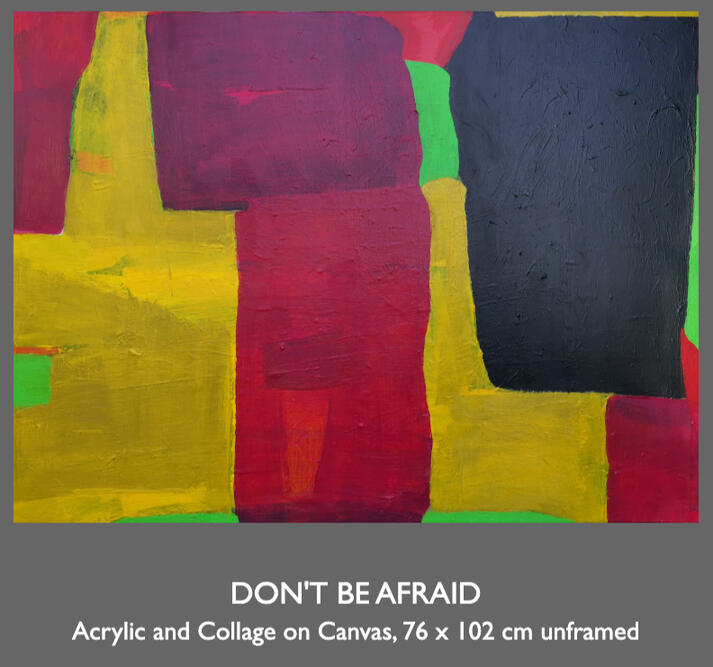

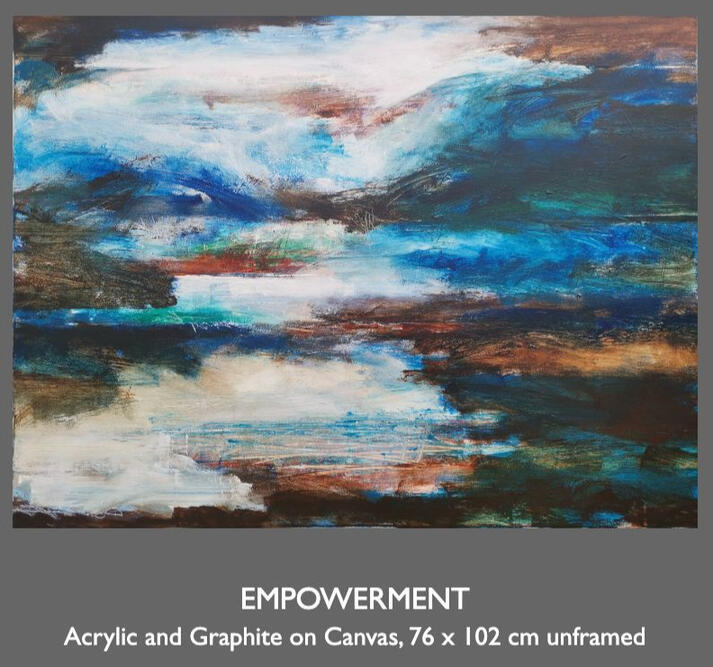

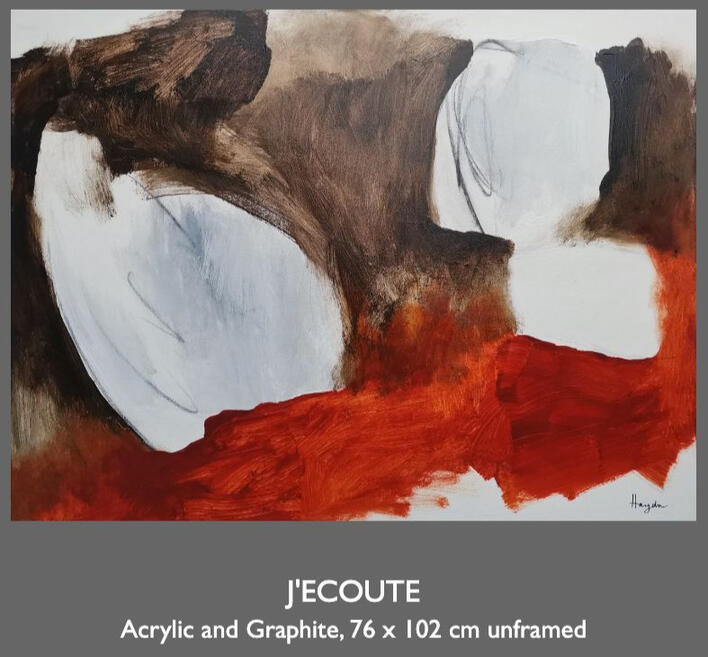

© 2021 by Haydn Dickenson

Haydn Dickenson is a pianist and painter. All paitings shown are by Haydn Dickenson. In 2006, before he started focusing his artistic work on painting, he published a recording of all solo piano works written by Peter Feuchtwanger. For more information, please visit his websites haydndickensonpiano.com and haydndickenson.com

In the autumn of 1983, I was a young pianist fresh out of university, embarking on my new career as a private teacher of Piano and Music Theory which I carried out by cycling to the homes of my students where I gave them their lessons. I've never been so slim, or fit, since; one of my families even used to refer to me as 'the skinny piano teacher'!My upbringing was one in which classical music was, in the words of the immortal Wanda Landowska, 'daily bread and spiritual food'. I played by ear from an early age, and I remember being obsessed with the ornate title pages of works such as Schumann's 'Carnaval' that were present in my home. Less ideally, I lived under the rule of a highly musical but controlling and dysfunctional father, a gifted amateur pianist who had studied with an assistant to Leopold Godowsky. He was a strict patriarch who alternately nurtured and restricted my musical development, and my childhood and adolescence was dominated by an increasingly distressing confusion in my impressionable young musical mind.As a youngster, I was able to to sight-read the Bach-Busoni Chaconne and other substantial pieces, systematically devouring major works at a young age. However, the paradox in my paternal parenting left me unstable emotionally and psychologically, with my musical and general self-esteem at a low ebb. Nothing pleased my father more than to see me master a major piece, but he cruelly dashed my confidence in even aspiring to become a professional pianist – a conundrum which I do understand to this day. I will always remember the occasion, at about the age of fourteen, when I knew I must make Music my life; it was while practising another transcription of the Bach Chaconne, by Brahms for the Left Hand alone. My father, at the time, was abroad.As time progressed, I became fixated on both pleasing my father and proving him wrong, a dual quest which drained my nerves.In the fullness of time I would meet an extraordinary human being who would change all that, one who would wash away the negativity and set me on a new, fascinating path.It was in the early 1980's when one of my former teachers, himself a fine international pianist, spoke a name to me which came to hold almost mythical status; a visionary pedagogue who had cured him of tendonitis in his elbow. The name was that of Peter Feuchtwanger.

As an enthusiastic young teacher and, on my stronger days still an aspiring pianist, I had joined EPTA UK and regularly attended wonderful seminars and events at Trent Park in London where I encountered the delightful Carola Grindea, founder of EPTA, among other luminaries. I became aware of video footage of the enigmatic Feuchtwanger lecturing and demonstrating at EPTA events and eagerly sought out these important documents in the EPTA archives.In the early 1990's, with my father seriously ill and his psychological grasp on me weakening, my spiritual need to develop and ascend as a pianist grew and grew. Like my former teacher earlier, I was experiencing fearful performance and practice-related pains, in my case due to an ill-trained pianistic mechanism mingled with a deeply troubled personal life. My practising was hectic, frenzied, frustrating, without direction. I was desperate to rid myself of the pain (mental as well as physical), and to lift myself onto higher levels. Asking colleagues for advice as to whom to approach for the highest calibre of guidance, many names were mentioned – Martino Tirimo, Alfred Brendel and Peter Feuchtwanger among them. To settle the matter, I went to visit my former teacher; of course, I hoped for one name in particular to be suggested – Peter Feuchtwanger!Peter Feuchtwanger was indeed the first name on his lips. I heard of how my teacher had reached a stage of being almost unable to play due to a form of tennis-elbow, of how he had encountered Feuchtwanger through EPTA, of a series of extraordinary exercises which had brought him to a pianistic rebirth. Emphasising that I should expect no ordinary experience with Peter Feuchtwanger, the words that echoed in my mind as I left his house were “radical, but fantastic”! I hurried home to attempt a few of the exercises that my former teacher had briefly shown me. I was already hooked!It was the spring of 1992. Knowing what I must do, I picked up the telephone.

“Hello”.....annunciated in tones that every student of Peter Feuchtwanger must recall and cherish – light but deep, soft, melodious, calm. I explained who I was, and by whom I had been recommended. An appointment was made. I remember this gentleman, already charismatic and exciting even over the telephone, describing how and where I should find him. “Ennismore Gardens – it runs parallel to Exhibition Road. Ring the bell and take the lift to flat 6”. That accent.......!

I arrived on the appointed day and time, nervous, insecure; but seeking to disguise this under some veneer of lightness. It was not an easy time in my life – I was in an unhappy marriage, the yoke of my father's controlling influence was a heavy one to bear, and I felt I had to act a part, to appear confident.How I remember ringing that doorbell, ascending the lift for the first time, the metallic clatter and scrape of the lift gate when I arrived at Flat 6! The door slightly ajar, I knocked.....and then he appeared, a gentleman unlike any I had met, looking a little – my first impression is enduring – a little like photographs that I had seen of Josef Lhevinne, opening the door but retracting as he invited me in. Kindly but cool, enigmatic, hypnotising. My first impression of the apartment was that I was entering another world, one of elevated experience, of art, of intellect, of human refinement far removed from the mundane.The two pianos awaited me, but I realised Peter sensed my unease. He offered me a coffee....I was glad to defer the moment at which I must play! I was motioned to one of the two instruments, the impossible and clattery action of which I would grow to love though by which I was horrified at first! We talked, and I played – terribly - pieces for which I was at the time ill-equipped.I was puzzled by the 90-degree-orientation of the piano stool – please do not remind me that I might have been so impertinent to attempt to re-align it! - but I am certain that I tried to raise its height. I may have been allowed this concession but of course, after some brief discussion I was urged to lower it again.I began to play a Scarlatti Sonata which I was approaching with impossible tension and seizure. Peter asked me to lower the stool once more, placed his hands on my shoulders and a miracle happened. Suddenly, I was playing this piece as if I was part of the piano, as if I was doing nothing at all. This was the first revelation – something so simple and yet so complex. I never looked back.I spoke to Peter of my thoughts, aspirations, passions, frustrations. Saying very little, he drew it all out of me. With in a few moments of meeting, he had identified and articulated that “I needed to prove something to my father”, an observation so acute and apposite that it astounded and moved me. I am not an extrovert person – I am given, rather, to reflection and inward sensation. Peter immediately saw through the breezy bonhomie with which I walked into his flat! “You come in all 'like this'...” he said, with an extravagant gesture, “But in reality you are hypersensitive”.I had known this man only ten minutes!Over the next fourteen years of tuition and many more of collaboration and friendship, I would gain an understanding of Music that I had never imagined possible. I would meet, through Peter, my future second wife and the mother of my daughter and I would prepare and record the first-ever complete album of his piano compositions.A new phase in my life had begun.

Haydn Dickenson

⇨ Read Part 2 here.

The Peter Feuchtwanger Society e.V. is in the process of setting up an archive of notes, sheet music, books, articles, photos and videos of Prof. Peter Feuchtwanger. They will gradually be made public. For more information, please visit our website.The Peter Feuchtwanger Society e.V. also hosts an annual Klaviersymposion in Feuchtwangen, Germany. The next edition of the symposium takes place from 02. to 04. April 2024.There is Book & DVD available with the piano exercises of Peter Feuchtwanger.And here you can find a list of pianists and educators who teach Feuchtwanger’s approach to piano playing with years of experience.

On Peter Feuchtwanger - Part 2

© 2021 by Haydn Dickenson

Haydn Dickenson is a pianist and painter. All paitings shown are by Haydn Dickenson. In 2006, before he started focusing his artistic work on painting, he published a recording of all solo piano works written by Peter Feuchtwanger. For more information, please visit his websites haydndickensonpiano.com and haydndickenson.com

Leaving the Penthouse after one of my early lessons, I floated on a cloud; I had just been told “One day, you will be quite marvellous”. Could this really be me?Over the course of the next ten years or so, I experienced countless hours in Peter's company that fundamentally altered my perception of music. Some were memorable for long, immensely detailed explorations of cornerstones of the piano literature, some for elucidations of how musical 'ancestry' is crucial to the understanding of a particular composer, some for introducing me to music that I had never before encountered. Many lessons were remarkable for the fleeting observations that they contained, as piercing in their accuracy as they were brief in their utterance. One of these was the occasion when Peter remarked on Edith Piaf's rubato in the song 'Milord' as being a perfect example of flexibility around the beat.There were innumerable times when Peter found the ideal way to bolster the confidence of a diffident student: “The playing of 'XYZ' in this Chopin Nocturne may be more accurate than yours, but yours is far more beautiful”. I remember too, Michael coming into the room one day just as I had finished playing the Chopin Variations op 12. I was playing, messily no doubt, but in a way that had never been possible for me before. Peter was so gently and warmly proud and encouraging, and Michael's exclaimed: “Ah, a true virtuoso now!”There were some standout lessons, of course, some life-changing episodes. Two such lessons that are especially etched in my memory were on the G minor Prelude and Fugue from Book 2 of Bach's 48, and the other, on Chopin's first Ballade. In these, astounded, I sat and soaked up the wisdom, the revelations, the profound truths, that made me feel that the fundamental secrets of music were being imparted that day. I will never forget these hours, and I consider myself blessed to have been allowed to share them with Peter.

Also quite incredible was the work we did on Beethoven op 101 and op 110, where Peter guided me towards a deep understanding of these miraculous works, an understanding that I had sought for years; he also showed me how the styles of earlier composers such as Bach and Handel infuse these pioneering late Beethoven Sonatas which, in turn, paved the way for much of the later nineteenth and early twentieth century piano literature. With Peter, nothing existed in a vacuum – all was connected.

Concurrent with these phenomenal individual lessons came an invitation from Peter to participate in his international masterclasses. The first that I attended was in Sion in 1992, followed by Weimar the following year.Before going to Sion, my only experience of masterclasses was those which I had seen on television, where (it seemed to me) the Master would do little more than give a lesson before an audience, offering no communication with those watching, moulding the student's performance into a simulacrum of his or her own. How different Peter's classes were! They were radical, always tailored to the student's ability and temperament, always searching for the core of technique as required, for the structure, for the sound, for the essence, and always involving the entire group in the lesson. I remember him gently scolding one participant for spending insufficient time in the class, as she was always practising her Schumann Symphonische Etueden to play them perfectly when her time came, an anecdote I often mention to my own students.When I went to Weimar the following year, I was immensely honoured when Peter asked me to assist in teaching his exercises to a group of students, daily. What heady days! What a summer of experience, of joy, of learning, of giving and receiving. At the same time, I was beginning to learn Peter's own incredible compositions. First came the Tariqa 1, then the second Tariqa, then the Dhun. Later came Studies 1, 2 and 3, and the Variations on an Eastern Folk Tune. Ah, The Variations! A most exceptional piano utterance if ever there was one – though of course Peter was extremely modest about this work.I remember the day when Peter sent me home with a cassette recording of his own performances of the Variations and the first three Studies. Suffice it to say that I had never heard piano playing like this – shimmering, coruscating, infinite in its colour and virtuosity - idiomatic representations of eastern styles communicated with genius through the medium of the piano. I hungrily began to learn these uniquely fascinating works, convinced that I had never before learnt anything so inimitably, addictively beautiful, or so complex and difficult!My cup was truly full when Peter asked me, in due course, to work towards the very first recording of his virtually complete piano output. This I finally achieved in the summer of 2006, and the recording remains a pinnacle of my life's work, the opportunity for which I remain eternally grateful.

As an adjunct to these professional reminiscences, I would like to share a pair of deeply moving personal anecdotes. The first of these concerns an occasion when I picked up the phone to call Peter. I have never enjoyed using the telephone, and any call made by me is somewhat of a feat! I dialled the familiar number though, and was surprised to hear no ringing tone at the other end – just a background noise, a little like someone chewing! Eventually, I spoke, just to check - “Peter?”

“Haydn?” came back the reply! Apparently Peter and I had called each other at the same instant, so no dialling tone had occurred! Ah, the miracle of synchronicity and close personal connection!In the article previous to this one, I recounted how I had lived through a troubled childhood and adolescence, dominated by a profoundly controlling father. Peter knew of this and was aware, too, that my father was dying of an incurable rare disease.My father died in June 1993. I was lying in bed, the morning after his passing, the telephone lying next to me as I was expecting family calls. The phone rang and, half asleep, I answered it. It was Peter; “Haydn, are you alright? - I just had the feeling that I must call you”. He knew. In the moments that followed, I told Peter of my father's recent passing.Peter Feuchtwanger profoundly enriched my adult life. I think of what I learnt from him every day, in my teaching, in my playing, sometimes just in my 'being'. I feel deeply thankful and privileged for my association with him.

Haydn Dickenson

⇨ Read Part 1 here.

The Peter Feuchtwanger Society e.V. is in the process of setting up an archive of notes, sheet music, books, articles, photos and videos of Prof. Peter Feuchtwanger. They will gradually be made public. For more information, please visit our website.The Peter Feuchtwanger Society e.V. also hosts an annual Klaviersymposion in Feuchtwangen, Germany. The next edition of the symposium takes place from 02. to 04. April 2024.There is Book & DVD available with the piano exercises of Peter Feuchtwanger.And here you can find a list of pianists and educators who teach Feuchtwanger’s approach to piano playing with years of experience.